We are very happy that you like sharing articles from the site. To send more articles to your friends please copy and paste the page address into a separate email.Thank You.

Printer-Friendly Version | Email Article

I recently read an interview conducted by Youki Terada with David Yeager, a psychologist on the faculty of the University of Texas at Austin. Yeager, author of the book 10 to 25: The Science of Motivating Young People, is well known for his research and insights about factors that reinforce intrinsic motivation in students.

In many of my writings I have addressed the topic of ways in which to nurture intrinsic motivation in our homes, schools, and workplaces. I have described theories of motivation, including Self-Determination Theory (SDT) proposed by psychologists Edward Deci and Richard Ryan. SDT emphasizes the importance of meeting four “needs” as a foundation for intrinsic motivation: belonging/connectedness; self-determination/autonomy, competence/mastery, and purpose.

Terada’s opening paragraphs immediately caught my attention. She reported that as a middle school teacher, Yeager assumed that the best way to engage students “was to put on a good show—Robin Williams standing atop a desk giving a rousing speech—but it wasn’t until he taught The Outsiders to his seventh-grade students that things started to click.” After they finished reading the novel, he asked his students to create conflict resolution presentations for younger students at the school.

Terada wrote, “The shift in their attitudes was dramatic—his students went above and beyond, conducting research and seeking critical feedback to produce top-notch work. They were motivated because the work they were doing tapped into their sense of purpose. It mattered.”

The words “purpose” and “mattered” resonated with me. Not only did they reflect one of the four needs posited in SDT, but they also captured a main component of what my colleague Sam Goldstein and I have labeled a “resilient mindset.” When children or adults are involved in “contributory” or “charitable” activities in which they enrich the lives of others, it nurtures their sense of purpose, intrinsic motivation, and resilience.

Yeager’s strategy to use The Outsiders as a launching pad to create conflict resolution presentations for younger students triggered a memory from many years ago. I have often noted that one of the most challenging positions I ever assumed took place at the beginning of my career. I served as principal of a school in the locked door unit of the Child and Adolescent program of McLean Hospital, a private psychiatric hospital in the Boston area. Within a few months in that role, I felt very stressed and burned out. The experience also proved to be a turning point in my career, an impetus to shift from a so-called “deficit model” with its narrow focus on what is wrong with people to an approach that was rooted in an appreciation of people’s strengths, using these strengths to develop strategies to reinforce confidence, hope, and resilience.

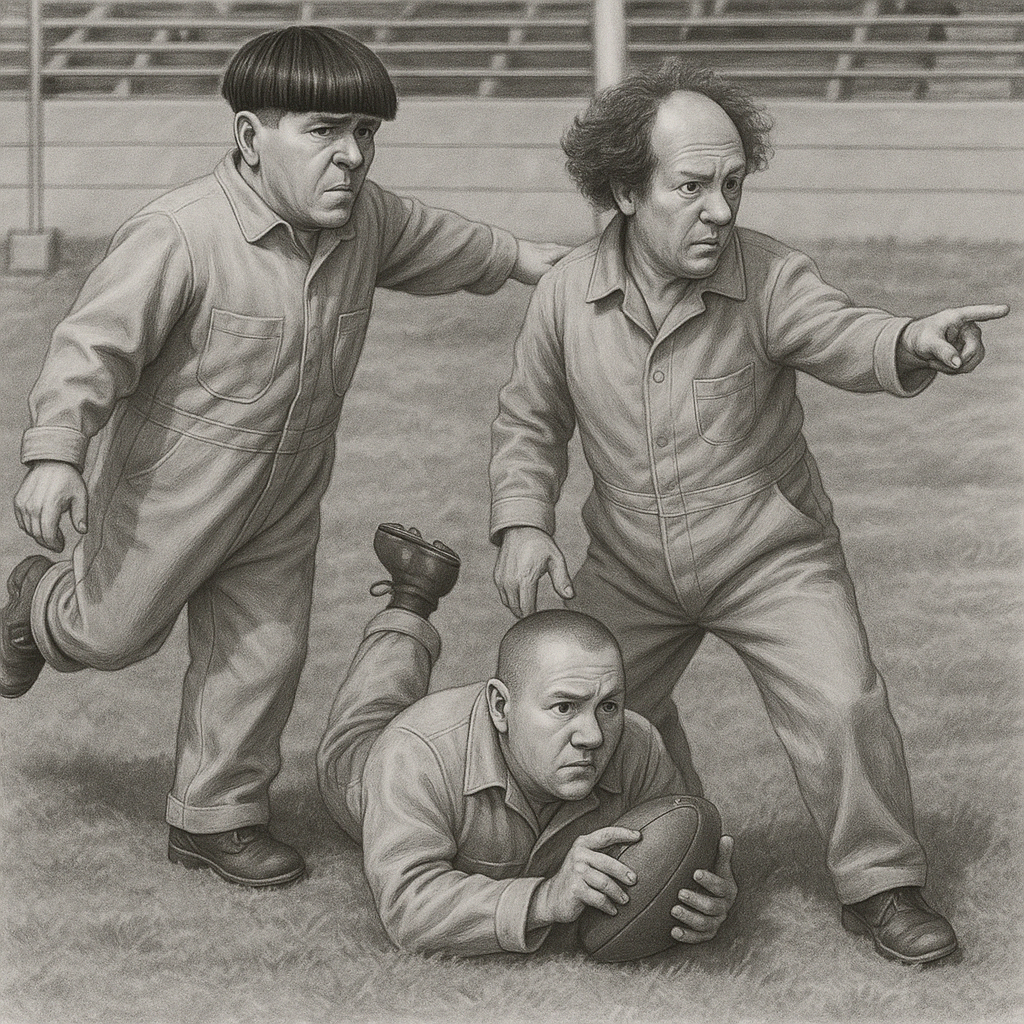

The Three Stooges as a Learning Experience?

The memory that was evoked by Yeager’s use of The Outsiders involved the Three Stooges and the creativity of several members of my teaching staff. Many of the patients at the school, especially the boys, would often imitate the Three Stooges by hitting each other on the head, often with their knuckles. Since a majority of these youngsters were in the hospital because of problems they had with their mood regulation and aggressive behavior, one hit would typically escalate to many hits as things quickly got out of control. Attempts to deal with these behaviors via rewards and punishments proved ineffective.

A few teachers approached me with a novel idea to lessen these challenging behaviors. When I first heard their idea, it seemed counterintuitive. My initial thought was that, if anything, it would increase rather than decrease these disruptive patient behaviors. The teachers proposed inviting their students to watch a couple of Three Stooges movies but with a different focus. They asked students to record how often they observed either verbal and/or physical expressions of aggression in the movies, a task that piqued the curiosity of the students. Similar to Yeager’s students creating a conflict resolution program, the students at McLean developed an “aggression curriculum” that included findings from their research about the Three Stooges’ movies and, very importantly, suggestions for dealing with anger in more constructive ways.

This project soon blossomed into a major event that I had not anticipated. With the input of their teachers, the students designed an exhibit with photos of the Three Stooges, graphs illustrating the number of aggressive acts that transpired in their movies, and proposed strategies to manage anger and aggression. We invited staff from throughout the hospital to visit the exhibit, and I was pleased by the number of people who did, including one of the top administrators at McLean. I was very impressed with the level of maturity the students demonstrated while describing different facets of the exhibit and answering questions raised by staff. Unlike the unsuccessful reward and punishment system we had been using, the behaviors of the students improved noticeably, as did their confidence in school.

As I spoke with the students about their exhibit, I realized their involvement touched them in several noteworthy ways. For many, it was the first time their strengths or what I call their “islands of competence” were displayed and the first time they felt they were making a positive difference in people’s lives. Terada’s words apply: “The work they were doing tapped into their sense of purpose. It mattered.”

In the interview with Terada, Yeager observed that some believe that either “young people can’t be motivated at all—or if they can, they’re motivated by short-sighted, selfish, hedonistic things like sex or drugs or getting likes on Instagram.”

Yeager’s next comment offered a powerful insight: “But the scientific view is that adolescents can be motivated; it’s just a different set of priorities. These priorities revolve around experiences of status and respect, the feeling that they are viewed as a person of worth and significance by others whose opinions they care about.”

As the school principal, I learned firsthand about students experiencing status and respect when involved with their Three Stooges project, although at that time what the staff and I did was not based on a theory. Rather, intuition, and perhaps a sense of desperation, played a role as we finally accepted that our punitive, crisis intervention approach was not working.

The Impact of a “Space Committee”

In one of my earlier books, The Self-Esteem Teacher (if I were to rewrite the book, I would change that title, especially given the negative connotations associated with the concept of self-esteem and the fact that the book dealt with strategies for reinforcing strengths, responsibility, caring, intrinsic motivation, and resilience in students), I described an example of providing students with status and respect. I did so in a chapter titled, “To Create a ‘Psychological Space.’” It concerned a major issue we faced during the first few months at our school—the ongoing vandalism that occurred.

I wrote, “Within the first few months, the baseboard radiator system was kicked apart. Obscenities were written on the walls. Wooden chairs were pulled apart. Overhead lights were broken. We resorted to a frenetic crisis intervention style rather than adopting a more thoughtful crisis prevention approach. This period probably represented the lowest point of my professional career—I felt helpless, hopeless, and ineffective.”

The vandalism occurred on such a regular basis that we formed a Space Committee of two teachers who had the task of making a list of the damage done each week that was then sent to Plant and Operations for repair. Damage that represented an immediate safety issue such as broken glass was reported the moment it occurred. Rewards and punishments proved ineffective. Frustration, anger, and a sense of helplessness were dominant emotions at our staff meetings.

And then a teacher raised the possibility of placing two students on the Space Committee, believing such a move would lead to greater student responsibility and lessen vandalism. Not everyone embraced this view. Another staff member argued it would be the equivalent of placing an arsonist on the fire department and, if anything, might lead to further destruction since it would place the spotlight even more brightly on the damage taking place. I could not predict if this suggestion would be effective, but what I did know was that what we were doing as a staff was not working. We decided to implement this intervention.

Initially, we had two students walk around the school with two teachers once a week. As they were to begin their responsibilities on the Space Committee, I spoke with the students. I emphasized that since the school was their space to learn, it was important for all of us to take care of this space. I expressed that their input would be invaluable. Looking back, I realize that my words served to empower the students and, in addition, their involvement on the Space Committee provided a sense of purpose.

What transpired during the next few weeks was impressive to behold. The level of vandalism decreased noticeably, obscenities were washed from the walls, books were stored on shelves and not thrown on floors. Other students were eager to be members of the Space Committee and, in response, we allowed different pairs of students to survey the space of the school several times each day. Eventually, students told me they could do their job on the Space Committee without needing the presence of teachers. I granted this request and the students continued to meet their responsibilities.

I interviewed students to learn why they valued being on the Space Committee. A couple of themes stood out. One was a sense of belonging, which is a key dimension of SDT and other theories of motivation. As one very insightful 12-year-old patient told me, “Being on the Space Committee helped me to realize that this was my space and I had to take care of it.” The second main theme is one that has been captured in many of my writings and presentations and it is a focus of Yeager’s as well: the importance of a sense of purpose. As a 13-year-old patient told me, “I felt good being on the Space Committee, and I was helping the school to be a nicer place to be in.”

Belonging and Purpose

These themes of belonging and purpose were highlighted in an article by Haleh Yasdi titled “Students with a Bigger Purpose Stay Motivated.” Yasdi wrote that Yeager’s strategy “purpose for learning” was an effective intervention and “teaches students to learn with the goal of making a broader, positive impact on the world. . . . Research shows that when students learn with compassionate or altruistic intentions, they view their academic work as more meaningful and beneficial. According to Yeager, this enhances students’ persistence, leading them to process the information more deeply and gain better recall of material.” Yeager also emphasized the importance of a student’s sense of belonging as a vital ingredient of intrinsic motivation and learning.

Yasdi observed, “Students. . . who have a greater purpose to learn will have a good reason to stay motivated even when their efforts aren’t followed by rewards and immediate success. In this way, purpose for learning presents an effective means for fostering a generation of motivated, socially conscious learners.” Yeager added, “Purpose is critically important and it’s tragically understudied.”

Yeager’s work reinforced my long-held belief in the importance of providing students with “contributory activities.” It is why one of the first questions I ask in my consultations with schools about challenging students is, “What is one thing that this student does at school that helps them to believe that they are making a positive difference at the school?” If teachers cannot think of one example, they are failing to utilize one of the most powerful interventions for strengthening student motivation and improving student behavior.

My Next Article

Given my decades-long interest in the concept of “mindsets,” another factor that drew me to Yeager’s writings was his identification of three different kinds of mindsets possessed by teachers that influence student motivation and performance. I will detail these three mindsets in my next article and also describe the relevance and importance of a sense of purpose, not only in schools but in many parts of our lives, including the workplace.